Aroma lab workbench, cabinet, and materials fridge.

In addition to my work as a researcher, I create custom scent applications for training, learning, academic knowledge mobilization, and cultural mediation that are intended for learning rather than wearing (i.e., commercial fragrance). My emphasis on the underlying materiality of aroma reflects an emphasis on learning ‘with and through’ materials in an active practice of inquiry rather than the preoccupation with their emotional, aesthetic, or physiological ‘effects.’ In his book about Making, Tim Ingold (2013) explains that “a material is not known by what it is, but by what it does, specifically when mixed with other materials, treated in particular ways” (emphasis, mine).

While I do call attention to the specific properties, characteristics, and qualities of particular aromatic raw materials I use in my work, I share Ingold’s emphasis on the conversation that emerges with and through materials (and environments) rather than ‘at’ them. This is in contrast with the manufacturing paradigm, whereby perfumes are an outcome of a client’s ‘brief,’ which refers to a pre-defined concept that is typically developed for purposes of marketing or branding commodity goods. While I have enormous respect for the extremely technical expertise required for the production of industrial fragrance and flavour manufacturing, my goals and purposes are quite different. In many cases, I am focused on a single raw material, cluster of related compounds, or living source of odour in the environment, which I scaffold for open-ended inquiry and meaning-making or as reference standards for deliberate practices of training.

My unconventional path to scent creation followed my founding of the Aroma Inquiry Lab in 2013, which began as a very small archive of raw, processed, and manufactured aromatic materials I had collected for purposes of teaching and learning. My interest in collecting these materials was inspired by insights developed during my doctoral field work studies of scent-themed environments, interactions, and practices with aromatic raw materials for cultural heritage mediation in Grasse, France and explorations of smell walking/mapping workshops in Toronto, Vancouver, and Marseille, France. After I defended my doctorate, I became interested in learning about the basic principles of perfumery, which I studied with American natural perfumer Mandy Aftel at her home studio courses in Berkeley, California. I later expanded on the foundations I learned from Mandy through a combination of self-study, further courses with other practitioners, and ongoing mentorship with other perfumers with a focus on mixed-media scent creation (naturals and synthetics).

As my scent practice is ancillary to a broad-based research program, which extends to many other contexts of practice/materials beyond aroma, I refer to myself as a researcher-practitioner, rather than perfumer or ‘olfactory’ artist. While my practice is technically perfumery, my chosen applications are intended for learning rather than wearing, or, in the case of olfactory art, as a prompt or trigger for physiological, psychological, or sensory ‘effects.’ Instead, my approach is a more basic call to aromatic context that resides at the other side of the nose, and that is explicitly concerned with learning in the present tense, rather than as a ‘playback device’ (Ingold, 2013) for affective inscription. Finally, as a lifelong outdoors enthusiast and (very slow) distance runner who trains all year round, I am interested in creating work that encourages more active inquiry into the sources of odours in the living world, rather than a substitute.

It is this more grounded orientation to the pedagogical and communicative affordances of aromatic raw materials (and scent-rich environments) that informs my orientation to practice. From this orientation, I relate to aroma as a missing modality of literacy, communication, and making rather than its purposes for consumption. From the standpoint of making, this reflects ways of knowing as doing things with and through raw materials, in contrast with the tendency to inscribe ourselves over a modality that is more spoken for than speaking.

Learning with-and-through

As I have observed in my research, it is very difficult for the public to access aromatic materials for purposes of open-ended exploration or deliberate learning inquiries. Such opportunities are rarely available outside of skilled professions involving scent, and this is often by design, as such skills and knowledge is often presumed to be the property of specific trades and academic disciplines rather than a literacy we are all capable of learning. Accordingly, my research-informed orientation to aroma in practice doesn’t defer to a single discipline (i.e., psychology, chemistry, biology, etc), industry or trade (i.e., fragrance/flavour, wine and spirits, food, etc), but emphasizes a more general orientation to th eknowledge, skills, literacies, and practices required to understand, and be able to do things with, aromatic raw materials. I argue that this is best approached at the site of making (production), rather than consumption alone.

My intentional use of the word aroma (rather than smell) reflects my ‘extra’ disciplinary emphasis on learning beyond disciplinary silos and industrial power bases to focus, instead, on the material and environmental sources of odours along with their properties, characteristics, qualities, and the associated costs and contingencies required to access and do things with them.

Some of the paradigms and perspectives that inform my orientations to my practice.

To learn with and through materials in practice is to acquire an understanding of scent from the inside out. This kind of orientation necessarily involves practical contingencies of time, labour, cost, practice, and access to knowledge of sourcing and using complex raw materials properly and safely. This is not only a distinction between modalities and sensations (i.e., sound versus hearing), but also the crucial differences between making and consuming.

As an academic whose creative practice is ancillary to a broad-based research program that extends to contexts of practice far removed from aroma, my orientation reflects a critical and pedagogical concern with the practical and on-the-ground contingencies required for the development of specific forms of literacy, competence, and skill that are constituted with and through materials. As I explain in my dissertation:

My emphasis on the pedagogical affordances of aromatic materials also examines how the preoccupation with affect (i.e, emotional or hedonic ‘effects’ of scent) often serves to obscure the kinds of literacies, competences that can be used to interpret, decode, and communicate things in deliberate, fluent, and skilful ways.

As I argue throughout my work, there is a gap in our attention to the environmental and material sources of odour in the world and of aroma as a modality that all of us can learn from the inside out, rather than second-hand sources of indirectly acquired (and increasingly unreliable) information. This also calls attention to the kinds of tacit literacies, competencies, skills, tools, and infrastructure that can only be developed in practice.

Scent in the Present Tense

My emphasis on the material basis of aroma that is engaged at the site of production, in contrast with their affective or hedonic sensory effects at the site of consumption, also shifts attention to the expertise, savoir-faire, and metier of skilled practitioners, such as cooks, professional tasters, sommeliers, chemists, and perfumers, whose competence is developed through intense and regular interaction and practice with and through aromatic materials and environments. If it were the case that mastery was merely an outcome of some magically ‘innate’ talent, rather than a lot of hard work, then we might all be master perfumers and Michelin chefs. While the narcissistic trope of sensorial exceptionalism continues to persist in popular culture, media stories, and movies, such narratives also serve to obscure the time, cost, and labour required to develop a working knowledge of thousands of individual raw materials and the skilled practices and regulatory knowledge that are required to formulate and compound these raw materials into safe and well-structured compositions. More plainly, aromatic knowledge is learned, not innate.

There are many ways of understanding aroma from the inside out that are common to humans, plants, and other species that are fluent interpreters of chemical communication. In these contexts, chemical compounds are a resource for survival that requires almost continuous inquiry and exposure to interpret. This kind of learned skill can be trained in humans just as it is trained in our non-human companions, such as SAR and K-9 working dogs, to identify and track highly specific odours at thresholds well below the capacity of the human nose.

Contrary to the popular myth that the primary significance of aroma is to ‘trigger’ emotional responses and memories, smell is most certainly not the ‘most’ powerful, or even effective, ‘cue’ for memory. In fact, scientific studies of olfactory-cued memory against other modalities found much stronger recall for visual cues, such as photographs (see Avery Gilbert’s What the Nose Knows, for an accessible, funny, and non-specialist explanation of the science of smell). The reality is, true olfactory ‘triggered’ memories are far less frequent and rarer than marketers (and journalists) might have us believe, but are also immediate, jarring, often unwanted, and sometimes, even traumatic. And like all memories, “subject to fading, distortion, and misinterpretation” (Gilbert, 2014, p.208).

The much-celebrated (but scientifically unfounded) Proustian trope, apart from its purposes as a literary device, is actually much closer to a laboured attempt at “recollection” (Gilbert, 2008) than an olfactory-triggered memory. But the Proustian trope also highlights the fetish of smell as a prompt for inscription, rather than its very important role in learning, characterizing, and evaluating sensory goods (i.e., product testing, quality assurance, and product development) and scent training of SAR and K9 units (which also make use of scented ‘reference standards’). The critique of romantic olfactory tropes also calls attention to the limitations of behaviourist stimulus-response theories that James Gibson long ago rejected and that continue to underwrite the faulty conceptual foundations of training schemes that rely on indirectly acquired taxonomies that are assimilated through rote memorization rather than understood with and through practice with raw materials. While the mere memorization of a particular form of specialized language may contribute to the appearance of mastery, the accrual of second-hand knowledge is not interchangeable with the development of genuine skilled competence that is constituted with and through materials in ongoing, usually daily, applied practice.

In my research into the development of learning that occurs in applied and skilled contexts of aromatic practice involving the use of material resources, I have observed how our attachment to cherished myths, anecdotes, and debunked claims (that continue to enjoy circulation in the media and popular culture) serves to obscure the more grounded expertise of applied practitioners whose facts might serve to contradict consumer fictions. As I argue in my chapter for the book Design with Smell, we’re never going to move much beyond the inherently solipsistic relation to scent as a mere ‘playback device’ (Ingold, 2011) for memories and emotions until we can learn to smell in the present tense.

Mediating literacy

During my doctoral research field work in Grasse, I observed (and smelled) first-hand how the most meaningful and relevant uses of aroma in the context of curation, interpretation, and public education require a full-time staff of mediators to provide one-on-one tutored explorations of raw materials and living sources of odour. In contrast with the use of scent as a ‘cue’ or ‘prompt’ to talk about ourselves, the practices I observed were primarily oriented to generating understandings of the source, provenance, and properties of living and raw aromatic materials and the knowledge and know-how (savoir-faire) required to transform them.

In Grasse, the perfumery museum’s trained cultural mediators guided visitors through rooftop greenhouses and a multi-acre garden (run by the perfumery museum) and facilitated hands-on workshops.

While I was initially curious about the scent devices before my research, my dissertation ultimately became an extended critique of device-driven approaches to scent features and the problems with poorly designed devices (that either absorb or mute the costly compounds inside, or else require almost continuous maintenance and malfunctions) and ultimately a call to aromatic context and the vital role of mediators in cultural heritage.

As I explain in my dissertation, there are many problems with leaving it to a device (or static novelty scent feature) to mediate a meaningful visitor experience with aroma. As I frequently observed, visitors rarely had any sense of what to do with the machines, their relevance to the collection, or any awareness of the skilled practices of sniffing. Yet when these same devices were scaffolded by the mediators, the visitor experience was much more interesting and meaningful, as the guides would not only provide important context but also help visitors make personal connections and compare their impressions with others on the tour.

Scent beyond ‘vapourware’

While the use of aroma in galleries and museums isn’t new, the preoccupation with delivery devices, novelty scents, and gimmicky, unsafe display formats that often upstage and obscure the nature and provenance of the scents inside, along with the often uncredited ‘ghost’ perfumers who are subcontracted to develop, formulate, test, and compound them. Indeed, almost weekly, there is another media declaration that scent is being used “for the first time” in an exhibit or gallery space. In many cases, such stories are closer to a form of viral marketing for a (yet another) scent delivery technology (device), which Canadian curator Jim Drobnick accurately characterizes as “high precision air fresheners” (Drobnick, 2006). As my colleagues and I argue in our paper Beyond Vapourware: Considerations for Meaningful Design with Smell (McBride et al, 2016), the entire conceit of scent technology is itself a type of vapourware marketed to gullible customers by way of bold claims about the ‘sensorial’ powers of their inexpensive and unconvincing pongs.

Accordingly, my work also implicitly (and often explicitly) critiques an emphasis on devices and gimmicky display formats that all but erase the provenance and specific nature of the scents inside, along with the people who do the work of creating them. Indeed, the preoccupation with visual display also mirrors the corporate fragrance industry’s emphasis on packaging, rather than the quality or safety of the chemical mixtures they contain. Finally, the notion that merely adding a scent feature will (magically) ‘trigger’ physiological or emotional response, however appealing, doesn’t really advance our understanding of aroma (itself) so much as reducing it to a kind of set ‘prop.’

By and large, the typical use case for the imposition of behavioural fragrance devices found in hotels, retail, and entertainment spaces is to promote and sell more … scent delivery technologies! This inherently aggressive format is not only unethical (i.e., we can’t choose not to breathe!) but also potentially a source of long-term contamination to the built environment (and everything within it). Unlike the more technical and higher quality materials and compositions used for the more passive formats associated with artisanal and olfactory art installations, corporate scent technologies rely on inexpensive, yet highly tenacious, aromachemicals that have been designed for industrial applications (such as fabric softeners) that are intended to embed into upholstery, clothing, along with many other places (like our hair, skin, and endocrine system) where these ‘sticky’ molecules don’t belong.

These issues call attention to the significance of relevant and research-informed design principles specific to aromatic applications. Given the high costs and long development time required to develop, formulate, test, compound original and highly technical scent applications properly and safely, it is therefore crucially important that this process begins with careful and critical examination of the particular ‘claims’ (and their corresponding benefactors) that underwrite ones selected ‘concepts’ and the degree to which these concepts either reinforce or challenge the usual tropes and conceits that are most often associated with appeals to neuroscientific authority. As I argue in my thesis and my chapter in the book Design With Smell, aroma can be engaged in more serious and pedagogical terms and regarded as a form of literacy that gives context and meaning to the world around us if only we could re-situate scent beyond territorial disputes between disciplines, industries, and their benefactors.

A focus on (high-quality) materials

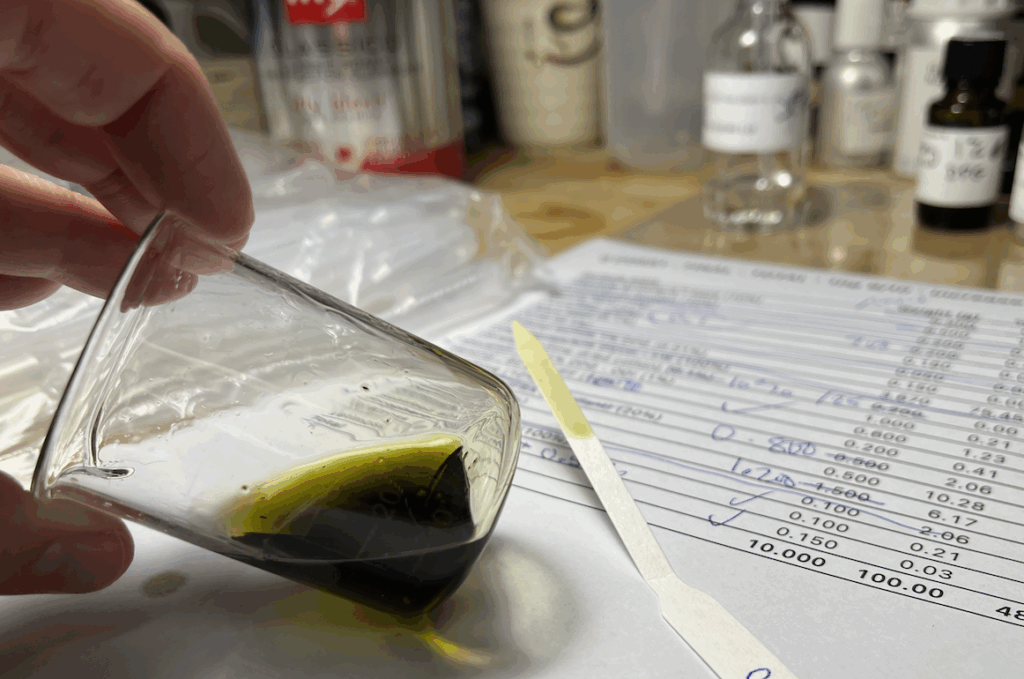

A dilution of seaweed.

It is this more materially grounded understanding of scent as a tangible (although invisible) form of information and a communicative modality that can contribute to context and literacy that inspires my own approach to scent creation and its use for cultural mediation.

To this end, I have developed original mixed-media scents (i.e., natural and synthetic) for scholarly knowledge mobilization, conference workshops, prototypes, training, and exhibits. While I do not manufacture commercial products for the consumer market, my work involves many of the same practices as professional perfumers, including compliance with regulatory guidance on safe limits for fragrance creation.

My scents contain rare, hard-to-find, and unconventional ingredients that are truly one-of-a-kind and intended to honour, rather than upstage, the artifacts they accompany. Over the past decade, I have developed knowledge of thousands of natural and synthetic raw materials from some of the finest raw materials manufacturers in the world, including Biolandes, Payan Bertrand, LMR, Robertet, Mane, Floral Concept, Berjé, Symrise, Firmenich, IFF, Givaudan, and Takasago. Given that I make use of many natural materials that do not scale for commercial production and also require extensive testing and special formulation software to ensure they fall within the regulatory limits, but also offer visitors an opportunity to experience materials that are very different from the corporate smellscape. In the case of natural materials I use, these are drawn from real environments, such as seaweed from the North Atlantic or fine pine absolute from Canadian trees, that can provide an authentic link to a particular environment, person, temporal period, or object many of us would not ordinarily have the opportunity to smell. I also make use of many fine man-made synthetic molecules and compounds that are often more realistic than some of their all-natural counterparts.

Even when I have a particular theme in mind, the most interesting work is developed in collaboration with my materials, just as a woodworker must enter into the grain of the specific wood they are using, so too is composition contingent on a conversation with the properties, qualities, and characteristics. As my mentors have often pointed out, the materials are actually our best teachers and will talk back to the projection or inscription of conceptual ‘ideas’ that fail to meaningfully engage with the possibilities and challenges of a given ingredient or composition.

Most recently, I collaborated with the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) to design, formulate, and compound four unique and historically themed scents for the AGO’s epic Making Her Mark Exhibit, which you can read about in my interview with the AGO’s Foyer Magazine. Later, I was asked to re-develop five custom scents for the AGO’s multisensory Art Cart, such as a whiff of Elvis for gallery’s iconic Andy Warhol painting, ‘Elvis I & II,’ and four other scents inspired by the works of Mark Rothko, James Tissot, Tom Thomson, and Gustave Caillebotte that are featured in the gallery’s permanent collections. Most recently, I collaborated with the AGO on two more scents for the exhibit David Blackwood: Myth & Legend.